A

framework for

transit-oriented

development.

Reinventing

the Suburbs

by Keith C. Hall

January 2018

originally published Feb. 4, 2017

on LinkedIn as "Reinventing the Suburbs as... Suburbs"

In Issaquah Highlands, increased density is accomplished through smaller lots and fewer streets.

Part One: How Seattle

Increases Density on its Transit Corridors

Seattle has no more land; the city is sandwiched between Lake Washington and the Puget Sound, while the region is squeezed between water and mountains.

King County is a big place, but much of it's land is Federally-protected as national parks and forests. Under Washington's Growth Management Act, an even broader swath of land is protected for mining, state parks and forests, and farms - permanently; there is no Oregon-style expansion of the urban area for future growth in King County.

It wouldn't matter if Seattle could expand its growth boundary; King County doesn't taper off into flat farmland... the region ends at large bodies of water and enormous mountains. If Seattle wants to grow, and there is huge pressure to do so, it must grow from within.

If Seattle isn't growing outward, then how does Seattle grow? Under Washington's Growth Management Act (GMA), all cities and counties are responsible for allocating growth - and accepting a share of that growth. In theory, they should be accepting a pro-rata share of jobs and residents to meet growth demands, but the reality is far more complicated than that, especially in the suburbs. For Seattle, a city where housing is in high demand, it provides a huge opportunity to redevelop its underdeveloped suburbs.

My neighbourhoodd is one of those that has historically lagged behind economically, and it still shows in what the city is willing to spend on its infrastructure, community centers, social services, and parks. In truth, I've spent my entire adult life living in predominately lower income and diverse neighbourhoodds that were, or would soon be, gentrifying into something else, and my neighbourhoodd in Seattle is no exception. I like living in areas of change (a.k.a. vibrant and dynamic cities). I also like living in walking distance of interesting places and near a transit stop with frequent service.

At the heart of West Seattle is Alaska Junction, a lively town center that serves as the neighbourhoodd's downtown, and it's just a 20 minute bus ride from the actual downtown Seattle. California Avenue is lined with stores, restaurants, and bars - some with new apartments on top (below right) and some older buildings with a mix of apartments and offices on the second floor (below left). There are two (soon three) major supermarket chains within a short walk of the future station; only one has surface parking (if you count the second level of a parkade as "surface parking") and all have lots of apartments on top (a QFC supermarket is shown below at the second traffic light under 5 floors of apartments). In a couple of decades, a light rail station will be dropped onto Alaska Street (somewhere near the center of the photo below). Transit-oriented development (TOD) came to Alaska Junction long before light rail transit (LRT), as long as you completely forget about the streetcars that once ran here.

Redevelopment in Alaska Junction is adding mixed-use development ahead of light rail, but the town center benefits from its history as a streetcar neighbourhoodd.

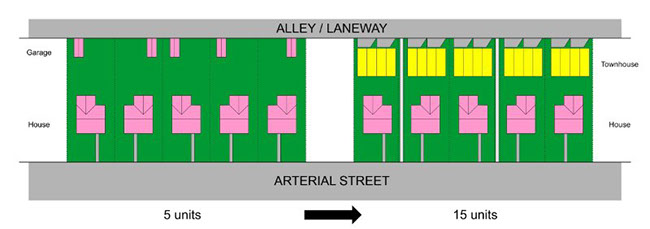

But outside of Alaska Junction, most of West Seattle is being transformed by the city's "LR" (low rise residential) zoning. The LR zone has been applied along arterial corridors that have frequent transit service, and the transformation has added quite a number of housing units to this inner suburb. The foundation of the LR zone is the 50' wide lot. One key advantage that Seattle has over most cities is that its arterial streets are generally only slightly wider than a local or collector street in other cities; people can live on a human-scale arterial street with a 30mph (50kph) speed limit.

Alki beach cottages have mostly given way to mid-rise apartments with a few townhouses and small-footprint houses mixed in.

Another key advantage that Seattle has over some other cities is the presence of rear alleys or laneways, coupled with a citywide grid network that is broken only by the city's (numerous) geographic features. Alleys are somewhat common in North America's urban grids, but they weren't built (or maintained) everywhere.

Example 1: Rear Laneway Housing

Rear laneway housing is a much-discussed topic in Vancouver as a way to make housing more affordable. From the map view above, Vancouver and Seattle are no different. In simple terms, you replace the rear garage with at least two townhouse (or other type of attached) units. In practice, the two cities are very different. Vancouver's street-facing homes are often impressive, elaborate multi-level structures, though many have been subdivided in to 3 or 4 apartments (there are a few of those in Seattle, too). In Seattle, the more common house is a modest street-facing home built for blue-collar workers and returning WWII veterans. In both cities, "affordable" laneway housing is only affordable to people making handsome salaries, but Vancouver does, for the moment, seem to prefer smaller rear garage apartments.

Rear laneway housing is placed on subdivided lots behind existing houses. A sidewalk between lots provides access to the main street.

Rear laneways, when well-maintained, are attractive residential streets (below). I attempted to buy one of the red townhouses shown above, but there are many buyers bidding on a very small inventory of available homes (I didn't get the house). The key element of this redevelopment approach is that you can easily triple the number of units along a major arterial without adding any street or utility infrastructure, but you must have a reasonable level of transit service to make up for the lack of parking and the increased density.

What was once the rear laneway, or alley, is now the front door for new townhouses.

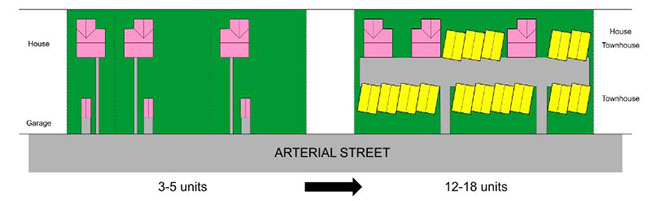

Example 2: Wraparound Townhouses

As with Example 1, this approach to infill retains the original single-family dwelling unit. The difference is that the original unit built was further back from the street, requiring that the townhouses be built in front. This approach also works where rear laneways weren't built (usually due to topography) or, in the case below, where they are so poorly maintained that no one would want them as the front entrance.

The single-family house (partially seen through the driveway) was set back far from the street, making room for a row of street-facing townhouses.

Typically, units have front doors facing the street with garage access from a common driveway in the center of the property. Although the units in "Example 1" (above) included only a single parking pad for each unit, units in "Example 2" have a more typical design with a single garage in each home.

The modest house is now wrapped by townhouses on three sides.

Examples 1 and 2 retain the original single-family house and added attached townhouses, but this is a fairly rare approach. The more common approach involves demolishing the original house.

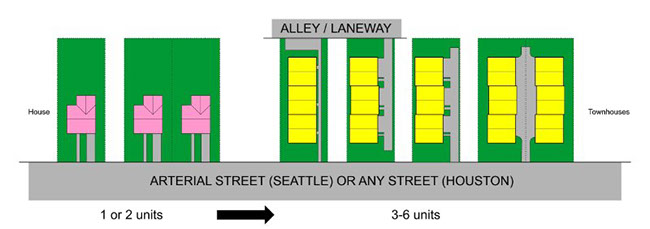

Example 3: Six Packs

One of the earlier forms of townhouse redevelopment involved converting one lot into three townhouses, with townhouse units aligned front to back on each narrow lot. The resulting design for a single lot was awkward, at best, and better designs emerged when two lots were merged to create a "six-pack." The improved design of the six-pack results simply from the consolidation of two driveways into a single, central access (wasting less land for the driveway). For a change of scenery, the photos below show a Houston 3-pack (left, shown in the side view from a vacant lot) and 6-pack (right). From a site plan and lot subdivision perspective, the Houston and Seattle approaches are very similar.

A three pack (left) and a six pack (right) in Houston includes houses much larger than those in Seattle. The 2-car per house parking requirement drives the size of the building footprint in Houston.

Although the six-pack has given way to newer designs in Seattle's LR zone, six-packs are still a common townhouse design in Houston's central city. Surely, I am not the only person who finds it interesting that the same housing typology has proven popular in two completely opposite land use planning contexts. One thing to note, townhouses are much larger in Houston than in Seattle, even though they aren't necessarily any more (or less) expensive (price depends on the neighbourhoodd).

Although the idea for this townhouse development typology in Seattle and Houston are conceptually identical, the outcomes, in terms of home design, are very different:

- Height limits in both cities are a function of building and fire codes. In Seattle, total height is further reduced by the zoning code (zoning height restrictions trump the higher building code allowance). A Houston townhouse typically has tall (standard height 9' or 10') ceilings inside the home, while ceiling heights in Seattle are lower, sometimes under 8', as a function of the overall building height restriction. Some Houston townhouses have 4 stories.

- Houston has a minimum 2-car parking requirement, since most townhomes have at least two bedrooms. Seattle townhomes typically provide only a single parking space irrespective of the bedroom count. Houston's parking requirement effectively does two things: (1) it causes the building area to cover a greater portion of the surface area of the lot, leaving less room for a patio, and (2) it requires the overall townhouse to be nearly twice as large as one in Seattle. Since Houston's larger building footprint often precludes ground-level patios for the rear units, outdoor space is often provided by 4th floor access to a roof deck (above left). However, rooftop decks have become common in Seattle, as well. Note that the two cities also differ in setback requirements, with Houston being more permissive about building close to or directly on the lot line.

- In Houston, townhouses have been built in many central city neighbourhoodds, irrespective of whether they are served by a frequent transit route (Houston does the same with its mid- and high-rise residential buildings; they are scattered all over the place). In contrast, Seattle has attempted to focus medium density residential development in transit corridors between commercial centers, while high density, mid-rise housing construction has been focused within commercial centers (high-rise is allowed only in and around downtown). Both cities are achieving higher density in their inner suburbs, but Seattle's approach is a far more effective way to create interesting and dynamic places in commercial centers (because people will live there) and effective transit routes (because more people will live along frequent bus routes).

- In the longer term, housing typologies in both cities could grow to be more similar. Continuing infill with mid- and high-rise buildings could help Houston achieve some level synergy within corridors and urban centers in some distant future. Likewise, Seattle may need to extend its LR zoning to streets beyond the first row of lots on arterial corridors and allow high-rise buildings outside the CBD area to meet longer-term housing needs.

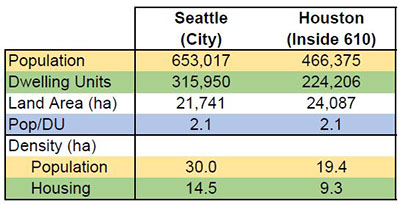

One last quirk of demographics is that, while Houston's newer townhouses are much larger than those in Seattle, they have the same number of occupants (overall average house sizes are reported to be nearly 2,200 in Houston and nearly 1,500 in Seattle). The table below shows a quick comparison of Seattle (city) and Houston (central city, or within the Loop 610 freeway). The city of Seattle and the area within Houston's inner loop are similar in size, and, as expected, Seattle is much more densely populated.

Table Source: Census, American Community Survey, 2015 (5-year average).

Example 4: "Cottage" Homes

Perhaps one reason the six-pack has lost favor in Seattle is that smaller homes can be built as "cottage homes." Cottage homes are essentially townhouses that have been built as detached single-family structures (obviously, what planners intended as "cottage homes" was very different from what builders built as "cottage homes"). Cottage homes are allowed under the same LR zoning as townhouses. In the photo below, 7 cottage homes were built on an irregularly-shaped lot at the base of a hill; each has a single parking pad and small ground floor patio.

Seven detached "cottage homes" fit on an irregular lot. Outdoor parking is located between the first and second row of houses; the 3 homes in the rear are terraced up the slope.

The example above did not result in a particularly attractive group. The front faces an arterial street, and there is no rear laneway to accommodate parking; thus, much of the remaining land area is devoted to asphalt. However, this configuration does satisfy the preference for affordable detached housing, as expressed by the fact that detached homes sell for nearly $100,000 more than nearby attached townhouses.

A six pack of detached "cottage homes" include 6 surface parking spaces on the rear laneway. The sidewalk provides access from the main street to the laneway with a modest garden area separating each home.

As a point of reference, one of these "affordable," newly-built single-family detached homes in a transitional neighbourhoodd costs just over $500,000 (well, they did in mid-2017, but by early 2018, you needed to add $100k to your home-buying budget), while a traditional new single-family house in that price range involves an unbearable commute from another county. Homes across the street (below) benefit from a rear laneway, allowing for a single pedestrian entrance at the front to access each of the six units from the arterial street with six parking pads on the rear laneway. Arguably, this arrangement results in a more attractive frontage from the main street-facing entrance.

Parking is a key reason that Seattle's LR zoned housing has evolved from the "six-pack" to the style of units shown above (which are still, in a sense, a six-pack configuration).

Links: "Cottage homes," or detached townhouses, were listed for around $600k in both Seattle (2,000sf) and Houston (3,000sf), but before you think you're getting a much better deal in Houston, take note of the property tax difference on these two homes ($1,600 a month in Houston versus $700 in Seattle). Also note that the Seattle house sold for over asking price, while the Houston house sold below ask.

- Seattle: Redfin Listing with floor plan (sold for $700k)

- Houston: Redfin Listing with floor plan (sold for $552k)

Example 5: Social Housing

One area that Seattle has excelled has been in the design of affordable and social housing units. In from single-family zones to mid-rise areas, Seattle has built social housing that blends in with higher-end market rate housing. In LR zones, social housing in the form of single-room occupancy (SRO) buildings are occasionally mixed in with new townhouses. The two units (below) provide 16 low income homes in a corridor with frequent transit service and easy access to downtown, jobs, and shopping.

Approximately 9 units are located in each building that is designed to look like nearby townhouses. There are two on-site parking spaces; parking is generally not a requirement along Seattle's major transit corridors.

Possible Conclusion (or just the end of this discussion)

A city wanting to produce moderate density urban housing can do so by rezoning single-family areas. A key to success is in both Seattle and parts of central Houston is the classic streetcar neighbourhoodd design; a 50' wide lot, coupled with a rear laneway on an urban street grid. It offers many more options for converting suburbs into higher density neighbourhoodds of mixed housing than greenfield and redevelopment areas. Seattle's LR zoning (link) provides one example of how moderate density redevelopment can be focused along arterial streets. Houston's lack of zoning illustrates another approach.

One area for improvement is better understanding the relationship between the three key sets of requirements that shape the form of housing in our cities: building standards, zoning codes, and parking requirements.

Houston's unzoned townhouses, despite having no height limits and minimal to zero required setbacks, are required by code to provide two parking spaces for housing units with more than one bedroom. Houston's requirement drives the market toward larger townhouses with larger building footprints, smaller yards, and more parking. Seattle's more permissive parking requirements allow a 3-bedroom townhouse to have only a single parking space, one that isn't necessarily attached to the house itself. This subtle difference in requirements may have allowed a much wider variety of homes in Seattle than have been built in Houston.

In Seattle, arbitrary height limits may increase building costs and construction waste because designers must create irregular interior ceiling heights (sometimes slightly under 8') to meet the overall exterior building height limit, requiring that builders hand cut standard materials to non-standard sizes during construction (leaving lots of scraps as wasted materials). In Houston, most materials can be used off-the-shelf with less labor-intensive customization or waste because builders aren't constrained by arbitrary height limits.

Many cities in the western and southern US don't have a framework for building townhomes at all, except as part of planned unit developments; thus, they are effectively banned in the inner suburbs where they would be in highest demand, and they are seldom built where allowed on the city fringe because they have lower market appeal. After all, what city-loving urbanite wants to live in "urban density" on the outskirts of a city where there is nothing to do and limited access to any place interesting?

A fourth potential challenge exists in determining whether there are enough properly-zoned lots to accommodate urban housing. Even in Seattle, the demand for these houses often exceeds the available supply of homes and land on which to build them. Consider that Seattle city's population grew 32% from 1980 to 2015, compared to Houston's 17% (inside Loop 610 only). Seattle restricts increased density to arterial corridors and growth centers, and it may need to adopt significant zoning changes to accommodate future growth. There is increasing resistance to upzoning in Seattle's neighbourhoodds.

Not surprisingly, not everyone wants land use to change.

In contrast, Houston's central city may have much greater capacity for growth without any change in policy. At Houston's lower growth rate, however, it may take a very long time feel a widespread sense of urban place in Houston's inner suburbs, but given that there's no zoning at all, Houston's residents face an impossible battle against higher density development.

a publication of