A

framework for

transit-oriented

development.

Reinventing

the Suburbs

by Keith C. Hall

April 2018

modified from Jun. 6, 2017

LinkedIn article

"A Quarter Mile Walk"

The most important determinant of success for a transit system is what is taking place at the stops and stations along the routes. This simple statement seems incredibly obvious, but many people fail to recognize that it takes a walkable city to make a transit city. This connection between transit and land use and walking seems especially lost on land use planners who are responsible for what happens next to transit stops.

aspirations for transit-oriented development

Planners and politicians alike often have high hopes that light rail and streetcar lines will be the sole cause of economic development in the form of transit-oriented TOD. They see a rail stop next to a big expanse of nothingness and dream of the opportunities for walkable mixed-use development projects that bring big cash returns.

If you're in Vancouver or Toronto, odds are that the zoning around stations will have changed to accommodate high density development long before the transit line opened, but zoning changes are far less likely in most American cities. Cities everywhere struggle to make suburban infrastructure conform to walkability requirements for TOD. For the most part, we can thank NIMBYs for undermining our transit systems, but that really doesn't excuse everyone else involved in the process for poor planning. After all, we still don't recognize the damage that parking does to transit stations (in the form of minimum parking requirements for development and as park-and-ride lots).

Surely, it must be a simple truth that for transit to provide an economic boost to an area, it must be responsible for delivering people to those destinations. Instead, we seem to be associating economic uplift with the embedded tracks carrying an empty vehicle in front of businesses.

seattle as a case study

Seattle is one of the exceptions; the city did not wait for a rail system to be planned before implementing TOD zoning. In fact, Seattle has promoted infill in most urban corridors that have frequent bus service, and many of the city's neighbourhoodd centers are rapidly adding mixed-use, mid-rise development projects. Over the next two decades, Seattle will add a number of new light rail stations as it builds out its expansive, $54 billion transit network. But with many of the extensions, infill stations, and new lines along the region's freeway network, practical opportunities for TOD may exist only at a handful of its rail stations.

Ironically, future opportunities for TOD along Seattle's future transit network appear greatest in neighbourhoodds that have already experienced significant redevelopment and already exhibit the characteristics of TOD. Most TODs in Seattle are served by lowly bus routes. In contrast, rail stations in areas that do not already have TOD are unlikely to develop with TOD in the absence of profound zoning changes and some form of economic uplift from the market and at least some public-sector financing.

In other words, it seems that TOD in Seattle "likes" to be around other TOD, and it doesn't seem to care that it's not near a rail transit line. Bus-based TOD works well, if planners plan for it (which may mean that land use planners actually have to believe that bus-based TOD works while transit planners have to make bus service very frequent). Moreover, TOD doesn't like cheap land; it likes to be in pricier neighbourhoodds with higher rental rates. Finally, TOD seems to prefer to have less parking in the neighbourhoodd, not more parking.

Obviously, there are some caveats to these statements. First, places like Alaska Junction and Ballard were built on the city's original streetcar system and continue to be served by frequent bus routes. That is, they were TOD long before we called it TOD. Second, Seattle promoted mid-rise mixed-use development in its neighbourhoodd centers years before the region decided to "connect the dots" with light rail. And finally, Seattle began focusing residential corridor density along its frequent bus routes by allowing the conversion of single-family to townhouses and apartments (see Part One of this series). Thus, Seattle's opportunities for TOD were established well before the light rail transit system was planned, both in distant history and with further upzoning in more recent years. But in a twist of irony, many, if not most, of the proposed transit stations in the Sound Transit 3 network are in areas that appear to lack any significant opportunities for TOD.

parking

Why does parking matter? Perhaps American planners don't believe people will connect to a rail station by bus. Canadians use bus-to-rail connections, but their bus service is usually much more frequent and often along "straight line" routes to stations. Americans probably just don't like wasting time waiting for meandering bus connections that arrive every 30 minutes and take 15 turns through neighbourhoodds before reaching the train station. Perhaps American planners don't really believe people will take transit to TOD (they won't if the service is bad). American planners are often skeptical that the development can survive without parking, so they refuse to ease up on the minimum parking requirements; but they also stick to the minimum parking requirements in fear that cars will overflow into surrounding neighbourhoodds (so they require parking, and therefore everyone does end up driving). Then, they add even more parking around rail stations. Like most American cities, Seattle's bus-to-rail connections aren't very good; it's an area in need of major improvements as the city expands its rail system.

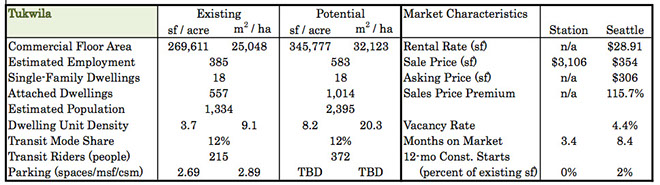

Seattle is somewhat of an exception not just in its land use requirements, but also in its parking requirements; Seattle has very low parking requirements, not unlike Toronto and Vancouver. Seattle's suburban cities have parking requirements more comparable to outlying suburbs in other American and Canadian cities. In the Seattle area, parking ratios range from 0.83 spaces per 1,000 square feet within a quarter mile of University Street Station to 4.63 in the quarter mile area of a bus rapid transit stop at Lynnwood Crossing, a suburban area surprisingly designated as a TOD through a zoning overlay. Tukwila's Southcenter Mall area has a ratio of 3.86 (the quarter mile radius from the southeast corner), while downtown Bellevue's ratio is 2.11 (a quarter mile from the Bellevue Transit Center).

Interestingly, stations with the most significant TOD opportunities tend to have low existing parking ratios, not more available parking that big box developers can turn into something else. More significantly, suburban cities might not be willing to relax minimum parking requirements, requiring significant amounts of parking at any future TOD.

the analysis

So why does TOD seem to want to be next to other TOD? I came to this conclusion as I evaluated TOD opportunities at a number of existing and future LRT stations in the Sound Transit network. These included different station types located in different land use contexts (excluding downtown):

- Future LRT stations on future LRT lines in Seattle urban centers and corridors (5 stations evaluated): Alaska Junction, Avalon, Ballard, Delridge, and Interbay.

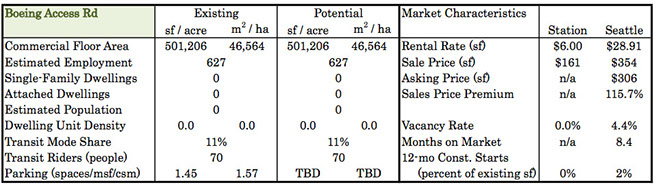

- Future LRT stations on the existing LRT line in suburban south Seattle (2 stations evaluated): Graham and Boeing Access Road.

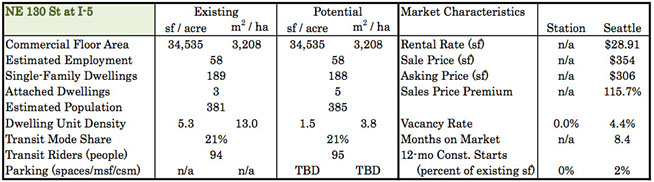

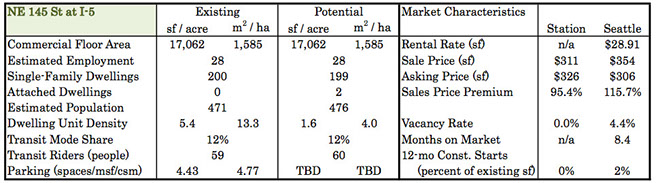

- Future LRT stations (freeway stations) on an extension of the existing LRT line in suburban north Seattle (2 stations evaluated): NE 130th St and NE 145th St.

- A future LRT station in an outlying suburb (1 station evaluated): Bel-Red.

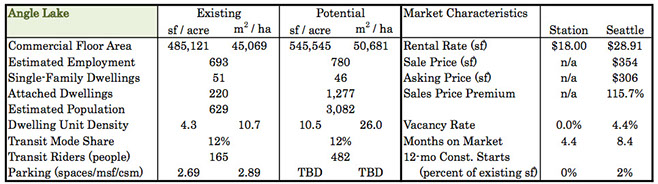

- Existing LRT stations in various contexts for comparison (3 stations evaluated): Capitol Hill, Tukwila, and Angle Lake.

Not surprisingly, stations along freeways and railways offer the fewest opportunities for TOD. Many of the region's existing and planned transit lines follow the easy-to-build route along a freeway or railway, and it makes the first statement in this article worth repeating: The most important determinant of success for a transit system is what is taking place at the stops and stations along the routes. If the stop is in the middle of or next to a freeway, there aren't likely to be many accessible destinations nearby. You might get good transit connections or a park-and-ride lot, but it won't be a busy stop, and there will be relatively few TOD or economic development opportunities.

To reach these conclusions, I made a few key assumptions, as described below:

- I did not assume that zoning would be changed at any station, and I only looked at the first quarter mile (400m) from stations. Ultimately, zoning may be changed at many of the stations, but there is no way to predict the outcome of future station area plans that do not yet exist, particularly when such changes are likely to face significant resistance in many of the neighbourhoodds. A future wholesale upzoning of station areas could mean that I have significantly understated the potential density of future developments in this evaluation.

- I only assumed that commercial floor area and mixed-use residential units in underdeveloped lots could reach the current average of density of fully-developed lots. This could have the effect of understating potential density in future developments where zoning does allow more intensive development. That is, I did not necessarily assume that actual development would approach the maximum allowable development density, just the level that already exists in the local area market.

- Opportunities to redevelop parking areas were identified in two ways: first are fully vacant lots used as parking, and second are underdeveloped lots (e.g. low floor-to-area ratio of potentially obsolete commercial buildings that could be redeveloped). It should be noted that Seattle has one of the lowest minimum parking requirements of any North American jurisdiction, and its parking requirements include mechanisms to reduce an oversupply of parking (as previously noted, this does not hold true in Seattle's suburban municipalities). Several stations evaluated outside the City of Seattle are identified as having the highest potential to redevelop parking areas; however, these jurisdictions also have excessively high minimum parking requirements. As a result, the amount of potential TOD is likely overstated, since much of the potential floor area would have to be built to accommodate parked cars.

- Two types of redevelopment of potentially obsolete buildings were identified: multi-family or low-rise zoned lots that contain 0-1 single family residences and low density commercial buildings (e.g. below 0.5 FAR, suggesting a single story building with a large parking area) built between 1940 and 1980; that is, they are old enough to be obsolete but not so old that they could have historic value (I'm not characterizing historic in the NEPA "any metal shed built in 1960 is potentially historic" sort of way).

- Finally, I represented the incremental benefit to the future transit system based on the potential increase in transit trips using existing transit mode share. This almost certainly underestimates future transit trips, because transit use tends to increase along a logarithmic curve as density increases, as long as the area is within a well-connected grid street network. In areas that lack urban street grids, high density development is less likely to have as significant an impact on transit (and active) mode share.

- One important thing to note is that Seattle, like many American cities but unlike Toronto or Vancouver, fails to develop proactive land use plans for its LRT transit stations at the early planning stages (Seattle tends to wait until construction starts, which may occur well after many developers have begun seeking development permits). Frequent bus corridors that have already been upzoned are already being redeveloped. Consequently, future station area plans that incorporate upzoning may come too late, as areas will have already been redeveloped to the extent currently allowed by the time the future rail station opens.

- Data are sourced from Costar and Commercial Broker Association (CBA) commercial real estate databases (March 2017). Graphics and photos are provided by the author, and the author assumes no liability for the accuracy of third party information.

conclusions

- TOD is likely to be more successful in areas that are already dense and can be made more dense. Too much parking (minimum parking requirements) is destructive to TOD.

- TOD can easily be built as a large number of small projects on small parcels. These often provide a well-connected street network (the urban grid) with built-in walkability. In contrast, large tracts of land that lack infrastructure near stations probably won't become successful TODs without a lot of up-front public-sector planning and investment (investment in well-connected streets). Furthermore, fewer developers can pull off the bigger projects.

- Expensive properties near transit stations are ideal for TOD. TOD is expensive, and developers take fewer risks building near other expensive properties (developers don't like building high-cost projects on low-value properties).

- TOD needs to have good access to transit, not just be near it or next to it (and we need to learn what that really means).

Part Two: How Station Areas (Nodes) are Transforming

the first group of case studies: the (rare) interesting stations

The case studies are divided into two sections, and this first section is devoted to the few stations where significant opportunities for redevelopment into walkable urban neighbourhoodds. Not surprisingly, these are historic town centers once served by the city's streetcar network where Seattle has recently zoned for higher density mixed-use redevelopment and improved bus service.

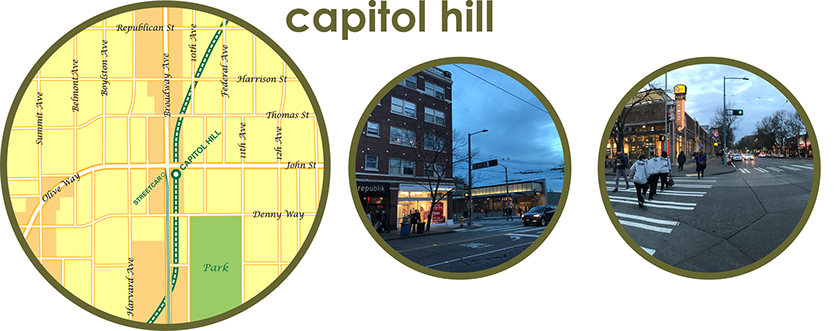

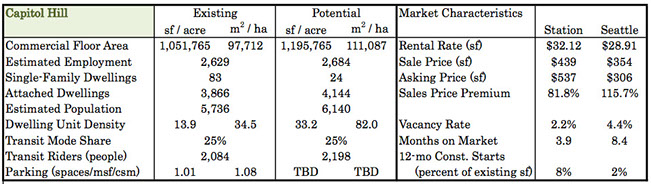

Among the existing stations evaluated, Capitol Hill is already intensely developed but still has significant potential for change. This seems somewhat counter-intuitive, but the area along Broadway is characteristic of a main street retail strip with one- and two-story buildings. Under current zoning, there is potential to add around 144,000 square feet (13,000 square meters) of commercial floor space and nearly 300 housing units within a 400m radius of the rail station. At current mode share, this would add over 100 daily users (people living or working within that 400m radius, not trips or boardings) to the transit system.

Both rental and sales prices are higher than the Seattle average; the parking ratio is very low; and new construction starts are significantly higher than the City's average, suggesting that the station area is already undergoing a rapid transformation into a higher density TOD. The lack of a large-scale parcel of land for redevelopment hasn't been an obstacle to redevelopment.

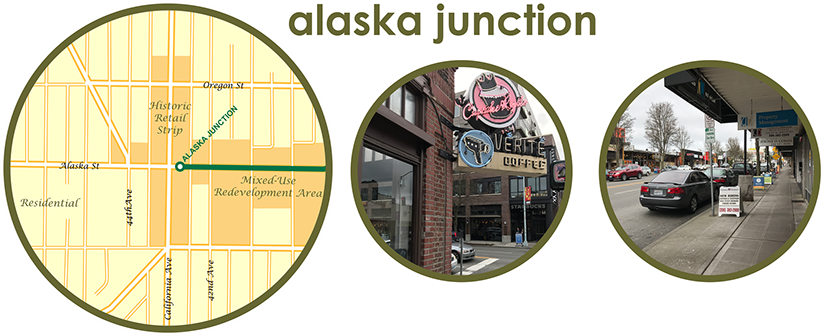

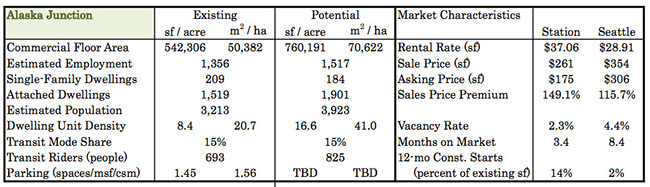

The future potential for redevelopment at Alaska Junction (a future station) is even greater than that of Capitol Hill. Another of Seattle's "main streets," the area retains a mix of low rise retail along California with single-family neighbourhoodds to the west. The area to the east of the future station has been rapidly redeveloping with higher density mixed uses, but there is still potential to add more than 200,000 square feet (20,000 square meters) of commercial floor space and nearly 400 housing units within a 400m radius of the rail station. At current mode share, this would add over 100 daily users (people, as defined above) to the transit system; though, it is expected that transit mode share will increase quite significantly with the introduction of rail service.

Although this neighbourhoodd is more likely to resist future upzoning than Capitol Hill, this analysis, as previously noted, is based on the development potential under current zoning. Rental rates at Alaska Junction are higher than the Seattle average; however, sales prices are lower, suggesting that this area offers a good value to real estate investors. The parking ratio is also low; and new construction starts are significantly higher than the City's average, suggesting that the area is undergoing a rapid transformation that may be complete long before the rail station is even built. Given the pace of current redevelopment, a station area TOD plan will come too late if the City waits until transit station design has been completed.

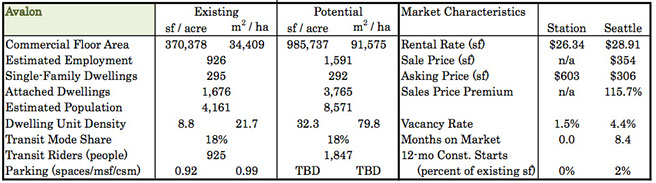

Unlike Capitol Hill and Alaska Junction, Avalon was historically a single-family residential area with a few low rise apartments and auto-oriented businesses along the main road, Faultleroy Way. In recent years, mid-rise residential buildings have replaced some of the lower density residential units, but gas stations, fast food restaurants, and even a lumber yard stand in contrast to the backdrop of newer mid-rise residential buildings.

Under current zoning, there appears to be an opportunity to triple the current amount of commercial space while more than doubling the existing residential inventory even without redeveloping the existing single-family residential areas. Redevelopment of commercial uses may provide an opportunity for the lower-than-average rental rates to increase with redevelopment (the extremely low vacancy rate already suggests a high level of demand).

However, obstacles to further redevelopment could occur from an unrealistic asking price for real estate, as well as the "staying power" of low density, high traffic retail uses (gas stations and fast food restaurants seem especially difficult to replace). From a transit perspective, this station would double the base of transit riders, adding more than 900 people (not trips) to the system even without an increase in mode share that could be expected with the addition of rail service.

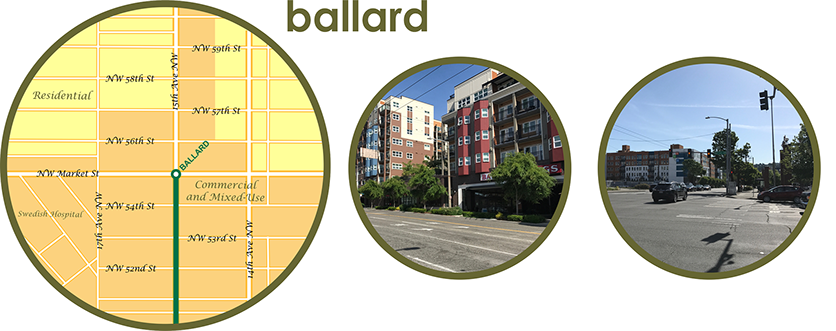

Like Alaska Junction and Capitol Hill, Ballard is focused along one of Seattle's traditional neighbourhoodd main streets. It has been an another area of rapid redevelopment, but it continues to have legacy industrial properties (marine and port-related) along the ship channel just beyond the historic downtown area (downtown Ballard lies approximately 500m southwest of the planned station, and therefore outside of the 400m station area). Ballard has already seen significant redevelopment outside of its largely intact historic main street, as reflected in the large commercial area and residential units in the station area. Nonetheless, there is still room to add a modest amount of mixed-use development.

Obstacles to redevelopment could occur from the high asking price for real estate, coupled with relatively low average rental rates. From a transit perspective, redevelopment around this station would double the base of transit riders, adding around 75 people (not trips) to the system even without an increase in mode share that could be expected with the addition of rail service. However, Ballard has a large commercial district with several major retail-oriented streets and a hospital, so the longer-term potential for ridership increases is probably understated here.

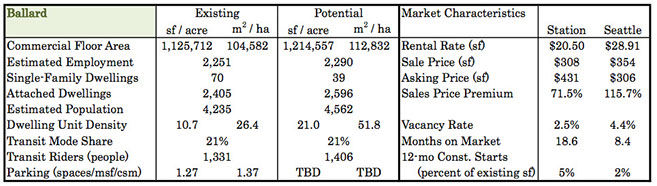

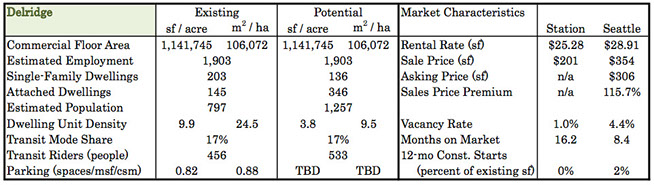

Delridge has a curious mix of suburban development in an area that has the framework to be a more urban place. There is a mid-rise and low rise office building, a suburban style shopping center, one mid-rise residential building, and a few historic retail buildings. In total, there is a significant amount of commercial space, but the lower-than average rents and extremely low sales prices likely reflect a less desirable location than other stations.

A key challenge in this area is building the transit line along the planned elevated route, which is wedged in between parks, sits in front of and above rather expensive new townhouses, and must cross a ravine and climb a steep grade to reach stops at Avalon and Alaska Junction. The train, as proposed, will be several stories above the rooftops of 3-story townhouses along a narrow street; it seems likely that homeowners might protest once they see initial design concepts for a heavy concrete elevated guideway in the sky.

The Delridge appears to have a very low vacancy rate, but current zoning will not allow any significant additional commercial or mixed use development to occur. In contrast, the area does have significant potential for the conversion of single-family houses into townhouses, likely adding some 75 people (not trips) to the transit system even without a change in mode share. This area appears to have an extremely low parking ratio, but given the large amount of visible surface parking around the office and retail buildings, this may simply reflect an error in the property database.

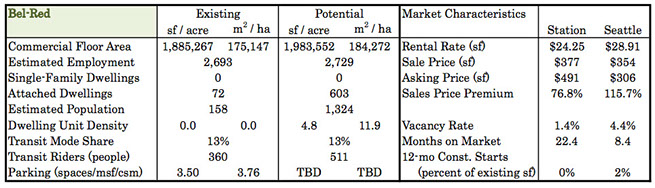

Bel-Red, the first suburban station evaluated here, is located east of downtown Bellevue. here appears to be an opportunity to add a modest amount of commercial space while massively expanding the existing residential inventory. This assumes that Bellevue can convert single-story big-box retail (most of which actually consists of surface parking lots) into mid-rise mixed-use developments.

Obstacles to redevelopment could occur from the high asking price for real estate (coupled with lower-than-average rents), as well as the "staying power" of low density retail uses (fast food and convenience store chains, budget hotels, and several large luxury car dealers). Two other key obstacles exist at this station: a lack of walkability on a suburban arterial street network and the city's minimum parking requirements, which could undermine any notion of TOD at this station. From a transit perspective, redevelopment at this station could double the base of transit riders, adding more than 900 people (not trips) to the system even without an increase in mode share that could be expected with the addition of rail service.

the second group of case studies: the (more typical) not-so-interesting stations

The second group of case studies include those where redevelopment of LRT station areas into walkable urban neighbourhoodds will be a more significant challenge. Some are LRT stations located along freeways, railroads, and golf courses (all are obstacles to access). Others, however, are simply located in areas with lower property values and commercial rental rates. In areas with well-developed infrastructure, some form of redevelopment is easily possible or even likely, especially where redevelopment is already taking place nearby (e.g. Graham). At other stations, the cost to convert provide local street infrastructure where none currently exists may not be feasible if they cannot provide an adequate return on the upfront investment.

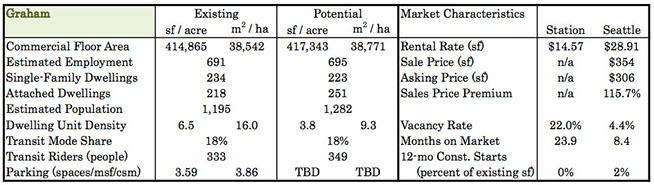

Graham is planned as an infill station on the existing Central Link line in the Rainier Valley. Stations to the north have seen significant redevelopment, notably the area around Columbia City. If Columbia City exemplifies Seattle's approach to TOD thorughout the Rainier Valley, then the overall change will be from a lower density to moderate density mixed-use (a mix of low- and mid-rise units). Given Central Link's regional mobility focus, stations are relatively far apart; therefore, Seattle's TOD occurs in spots around stations. Areas in between have not seen significant redevelopment. Graham provides one more opportunity "spot" for TOD, once the City has rezoned it appropriately.

The Central Link LRT would have been a straight north-south route, but the route as built makes a semicircle loop to serve the Rainier Valley. While the rest of the line runs largely in its own right-of-way with few grade crossings, the Rainier Valley segment is at-grade in the median of Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. This central segment of Seattle's LRT makes for a slow ride between Seattle and its airport (it even takes longer than the former 194 tunnel bus that once ran between downtown and the airport). Ideally, the LRT system should have been Seattle's regional (and rapid) "train" service, while the Rainier Valley should have been built as a streetcar line with stops every one-third of a mile to provide access and be the catalyst for a continuous corridor of redevelopment. But that did not happen.

Interbay is the rather unexceptional area between two very nice neighbourhoodds, both of which sit on top of hills. To the east is Queen Anne; to the west, Magnolia. Interbay is an unimpressive mix of retail and office along 15th Avenue and industrial along the railroad corridor below these two exclusive neighbourhoodds. There are some interesting things in the area, including a fish market and marina, but mixed-use shows up in this corridor mostly as a hodgepodge mix of crap. Maybe it will be more interesting someday, but the higher-than-average sales price and lower-than-average commercial rental rates may prove an obstacle to redevelopment in the near term.

Boeing Access Road is planned as a future station on the existing Central Link line, and this is arguably among its worst stations for TOD. Sandwiched in between (and elevated well above) railway and highway rights-of-way, this station is designed primarily as a connection between the Sounder commuter rail service and the light rail system. It should serve that purpose well during peak periods when commuter trains are running, and it may connect a few buses, as well. It is a shame that a key transfer hub cannot serve as a destination (only 70 riders with no real potential for growth), but poor street connections to low value real estate are not the ingredients for successful transit-oriented development.

Get out your golf clubs, bring your dog, and take a trip to NE 130th Street. Lacking space even for a park-and-ride, this station may offer convenience to no more than a few houses in one of Seattle's lower density suburbs. Much of the land area in this zone is occupied by I-5 and parts of very large golf courses and parks, including an off-leash dog park. Residents in this part of Seattle have strong NIMBY tendencies, so a major rezoning will prove a challenge. And sorry, dog owners, Metro (Seattle's main bus operator) allows dogs of all kinds on its buses, but Sound Transit prohibits pooches on trains.

Serving the northern end of a golf course that stretches from just north of 130th, the 145th Street stop serves single-family residential areas, a small park-and-ride lot, a school, and several large churches. As with 130th Street, it is hard to imagine that major land use changes will be easy to accomplish. Moreover, there is no shortage of parking for those who will continue to drive to the few destinations in the area (note that parking calculations indicated below exclude those provided at the school and park-and-ride lot).

Angle Lake serves a major park-and-ride lot and provides a connection to airport-area commercial land uses. There is significant multi-family housing inventory, as well as a large area of undeveloped land partially surrounding a Federal detention facility. With a prison and the south end of a busy airport runway as neighbors, a quality TOD seems unlikely to emerge here, even though zoning provides plenty of growth capacity.

Located near the northern boundary of Seattle's primary airport, this existing station is home to a busy park-and-ride lot. There are signs that commercial strip centers may redevelop as mid-rise mixed use developments (okay, there is one sign... one project is happening just north and outside of the 400m station boundary). Walkability in this area has improved, thanks to pedestrian access improvements on Tukwila International Blvd., but the station itself is focused on its own parking lot instead of the street frontage. Sound Transit could undertake a major joint development initiative on its parking lot, giving this area a much-needed redevelopment catalyst. This area seems to have potential, but financial data are somewhat sparse, making any analysis a bit difficult. Even with thoughtful planning, the access constraints around the station will be a challenge to overcome (pedestrians can only enter the station from a side street).

in conclusion

I started with a short version of this conclusion, but here it is in more detail, along with some additional thoughts.

- We often think that the best TOD opportunities are on large greenfield sites or as redevelopment of large shopping centers. The apparent truth is that TOD likes areas that are already dense, areas that can be made more dense. TOD doesn't like to be built with or near a lot of parking, and minimum parking requirements seem to be destructive to TOD.

- We often think we need to assemble small parcels into larger tracts of land for redevelopment to create TOD; that is, we tend to think that small parcels are unsuitable for large-scale, dense development. The apparent truth is that TOD can easily be built as a large number of smaller projects on smaller parcels by a number of smaller developers. In fact, TOD appears to prefer small parcels located within a well-connected street network (the urban grid), and this may be a truth because it allows walkability between destinations and to shared parking located somewhere else in the vicinity (often paid parking that is not necessarily provided as part of the TOD).

- We often see lower-value properties near transit stations as ripe for TOD, especially if we can finance improvements with a tax-increment finance district. The apparent truth is that TOD is expensive, and it likes to be near other expensive properties. It doesn't seem that developers are willing to risk investing in costly TOD projects that will be surrounded by low-value industrial our outdated retail centers. This is not to say that redevelopment strategies are futile; they just take a lot more thought, planning, and investment from the public sector - beyond just what most developers are able to do - to influence land use change in a wider area.

- Another truth is that transit infrastructure must accommodate a delicate balance between speed, directness, access, and frequency of service provided. In other words, we need to start planning the infrastructure to support the desired service (and by "we" I mean Americans need to at least start thinking about the service we want to provide before finishing the design process, because Canadians already do that, which is probably why their systems carry a lot more people than ours do). We often think that the speed of transit service is the most important factor affecting LRT system ridership, but we tend to undervalue access. In contrast, we tend to overvalue access when we plan streetcar systems while forgetting the most basic transit operating principles. Thus, we end up with LRT systems with straight-line routes along freeways that serve nothing along their routes, linked to meandering streetcar loops that stop everywhere at slower-than-walking speeds. Local politics, NIMBYs, and NEPA processes conspire to give us routes that loop between destinations with added zig-zags to avoid controversy. But our shortcomings on this front is really a different discussion for a different day.

a publication of